Château of Vauvenargues

The Château of Vauvenargues (French: Château de Vauvenargues) is a fortified bastide in the village of Vauvenargues, situated to the north of Montagne Sainte-Victoire, just outside the town of Aix-en-Provence in the south of France.

Built on a site occupied since Roman times, it became a seat of the Counts of Provence in the Middle Ages, passing to the Archbishops of Aix in the thirteenth century. It acquired its present architectural form in the seventeenth century as the family home of the marquis de Vauvenargues. After the French Revolution it was sold to the Isoard family, who despite their humble origins eventually installed their coat of arms in the chateau. Nineteenth century additions include a ceramic maiolica profile in the Italian Renaissance style of René of Anjou, one of the former owners, and a small shrine containing the relics of St Severin.

In 1929 the chateau was officially listed as a historic monument.[1] In 1943 it was sold by the Isoard family to three industrialists from Marseille, who stripped it of its furnishings and mural decoration, some of which still survives in the Château of La Barben. In 1947 it became a vacation centre for a maritime welfare institution.

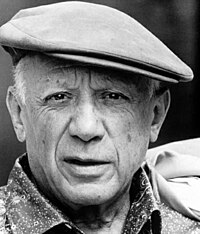

It was acquired in September 1958 by the exiled Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, seeking a more isolated working place than his previous home, "La Californie" in Cannes. He occupied and remodeled the chateau from 1959 until 1962, after which he moved to Mougins. He and his wife Jacqueline are buried in the grounds of the chateau of Vauvenargues, which is still the private property of the Picasso family. Their tomb is a grassy mound surmounted by La Dame à l'offrande (1933) (English: Woman with a Vase), a monumental sculpture that previously guarded the entrance of the Spanish pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1937.

History of chateau

[edit]

The present chateau is situated on a rocky knoll rising 440 m above a narrow gorge of the river Cose. During the Roman occupation of Provence, when Vauvenargues was known as "Vallis Veranica",[2] the site was occupied by a fort. The medieval castle was built over the Roman site; one large room with walls 2 to 3 m thick dates from this period. The castle passed from the Counts of Provence to the Archbishops of Aix in 1257, when Isnard II of Agoult and of Entrevennes ceded the property of his wife, Beatrix of Rians, to Vicedomino de Vicedominis, Archbishop of Aix.[3][4] In 1473 ownership passed from Oliver of Pennart, Archbishop of Aix, to René of Anjou, the "Good King René", who two years later bequeathed the castle to his physician, Pierre Robin of Angers.

The castle was successively the property of the Lords of Cabanis, of Jarente and of Séguiran, until 1548, when ownership passed to François de Clapiers after his marriage to Margaret of Séguiran. It remained in the de Clapiers family for two and a half centuries. The de Clapiers family's roots go back to Spain: Jean de Clapiers moved from Andalusia to Provence in the fourteenth century.[4][5] Between 1643 and 1667, while preserving the outer defensive walls, the medieval keep was radically transformed into a manor house or gentilhommière by Henri de Clapiers, a cavalry officer, who later in 1674 was appointed first consul of Aix and state prosecutor.[4]

For his exemplary conduct during the Great Plague of Marseille of 1720 which devastated Provence, Joseph de Clapiers was given the hereditary title of Marquis by Louis XV. The most famous of his sons was the celebrated Enlightenment philosopher and moralist Luc de Clapiers, admired and befriended by Voltaire and Marmontel. He died prematurely at the age of 32, almost blind and disfigured by smallpox, before his writings had achieved due recognition. He recounted how, while reading the classics as a youth in Vauvenargues, feeling suffocated, he would "leave his books and rush out as if in a rage to run as fast he could several times around the very long terrace... until exhaustion brought an end to the attack."[6]

After the French Revolution, the château was sold in 1790 by the third marquis of Vauvenargues to the Isoard family. Although of humble origins, the family achieved preferment during the First Empire as a result of the friendship between Lucien Bonaparte and the abbé Joachim-Jean-Xavier d'Isoard, elevated to Cardinal in 1827, Archbishop of Auch in 1828 and Archbishop of Lyon just before his death in 1839.[7] The cardinal had a small oratory installed inside the château to house the relics of St Severin, a gift from Pope Pius VII.[8]

The château stayed in the Isoard family for 150 years until its sale in 1943 by Simone Marguerite d'Isoard Vauvenargues to three industrialists from Marseille. Despite its listing as a historical monument in 1929, all the furniture and a large part of the interior decoration including the magnificent Provençal embossed polychrome gilded Córdoba leather paneling lining the library and ceremonial reception room, was removed by the buyers. In 1947 it was transformed into a vacation centre for a maritime welfare organization, l'Association pour la gestion des institutions sociales maritimes.

Picasso's chateau

[edit]J'ai acheté la Sainte-Victoire.

After passing through a series of other owners, the vacant property was shown in September 1958 to the Spanish painter Pablo Picasso by the collector and art critic Douglas Cooper. Picasso was returning from a corrida to attend an exhibition of his own works at the Vendôme pavilion in Aix-en-Provence; he was so taken by his first impressions of the chateau that he bought it within a week.[9] Already from his first visit to the chateau, Picasso was aware of its history, in particular its connection with Luc de Clapiers. He moved into the chateau in January 1959 and thus embarked on a new era in his career. He was particularly proud to live in the shadow of Mont Sainte-Victoire, one of the favourite subjects of the French painter Paul Cézanne, a native of Aix. A well-known anecdote has been passed on by his agent Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, whom Picasso informed that he had bought the Sainte-Victoire. When his agent asked him which one, thinking he meant one of Cézanne's painting, Picasso replied with satisfaction, "La vraie"—the real one.[10] During his period at Vauvenargues, Picasso would never paint Mont Sainte-Victoire; the few landscape paintings he produced there were of the village of Vauvenargues opposite.[11]

Kahnweiler asked Picasso on his first visit to Vauvenargues whether, even with the magnificent setting, it was not perhaps too vast or too severe. Picasso replied that it was not too vast, because he would fill it, and that it was not too severe, because as a Spaniard he liked sadness.[12] When another art dealer Sam Katz paid him a visit, Picasso proudly proclaimed, "Cézanne painted these mountains and now I own them."[13]

At La Californie in Cannes, purchased in 1955, the view to the sea had been blocked by the construction of high rise apartments; socially too many demands had made on his time there by journalists and other visitors. Picasso had bought Vauvenargues not as a holiday retreat, but as a permanent home where he could work undisturbed. Apart from the installation of central heating, the standards of comfort in the chateau remained rudimentary. In April 1959 he moved his whole personal art collection from bank vaults in Paris into the chateau, overseeing and helping in the unpacking and hanging of the paintings. Among the artists in his collection were Le Nain, Chardin, Corot, Courbet, Renoir, Gauguin, Vuillard, le Douanier Rousseau, Matisse, Braque, Miró, Modigliani and Cézanne, of whom he had three oils and a much prized watercolour.[14]

Picasso brought all the bronze sculptures from his garden in La Californie, which he arranged on the terrace in front of the principal façade of the chateau and in the entrance hall. Either side of the balustraded stairs leading to the front doors are fountains spouting water from grotesque sculpted heads from Portugal. Apart from the tomb, there are no longer any sculptures on the terrace; the Hungarian photographer Brassaï recorded that Picasso with the help of his children would create a patina on outdoor bronze sculptures by urinating on them.[15]

une cochonnerie Henri II, rien de plus. Mais comme c'est beau !

The Provençal dining room was the most lived-in part of the chateau. The traditional farmhouse table, with its simple wooden benches, stands on a floor tiled with Provençal octagonal brick red tomettes. On the mantelpiece over the marble fireplace stands a giant lifesize photograph of Picasso, placed there after his death by Jacqueline, who was not yet his wife when they first moved in. She was less taken with the chateau, complaining that it was too large and draughty. In the same room are two objects which Picasso often used in his paintings: a mandolin acquired in Arles, which figures in a series of still lifes, and a large black dresser (French: Buffet) in the style of Henri II.

In the nineteenth century room of Cardinal d'Isoard, Picasso installed a medallion cabinet, left to him by his friend Matisse, who used it for storing prints and drawings. In his studio, as well as all the artist's painting materials, are a set of large wooden skittles, a gift from Marc Chagall, as well as two chairs that Picasso painted almost as soon as he arrived in the colours of yellow and red for his native Spain and green for the surrounding forests of Vauvernagues and Mont Sainte-Victoire. Facing west with three spacious windows, his studio is the largest, grandest and best lit room in the chateau; like the library downstairs, it still has its original highly ornate seventeenth century sculpted plasterwork and mouldings, but all rendered in bright white. Picasso also brought in two industrial lamps to guarantee the quality of light. Commentators have said that Picasso tried to recreate at Vauvenargues the same conditions as in Spain: the intense light, the brilliant primary colours, the austerity and the rugged setting.

The bedroom of Jacqueline has a simple bed in the defiant yellow and red colours of the Catalan flag. There is a swirling red and black carpet, designed by Picasso himself and taking up a theme familiar from his lino cuts. The walls of her bedroom were left in a partially painted state, as Picasso wished to live in the chateau as he found it. One wall of the adjacent bathroom has a bucolic frieze painted by Picasso into the plaster, a large scale version of his many bacchanalian scenes, with a faun playing on pipes amid greenery. Green garden furniture was later added by Jacqueline.

In fact Picasso only occupied the chateau for a relatively short period between January 1959 and 1962, with several interruptions. Nevertheless, all the works of art he produced there bear the indelible marks of Vauvenargues, one of the high points of his career. Among the different themes, he painted various portraits of Jacqueline, jokingly styled Jaqueline de Vauvenargues, often with infant figures — the children they would never have; a series of bacchanalian scenes, many of them in lino cuts, with fauns and centaurs, rekindling themes from an earlier period when he lived with Françoise Gilot in Antibes; and a series of paintings and drawings based on his own reworking of Déjeuner sur l'herbe by Édouard Manet.

During this period Picasso acquired the mas (farmhouse) of Notre-Dame-de-Vie at Mougins, where he moved permanently in June 1961. He came back from time to time to Vauvenargues, but had to stop following a serious operation in 1965. After that Vauvenargues became a stopping-off point for Picasso on his way to corridas in Arles or Nîmes.

After Picasso

[edit]

Picasso died at his hilltop villa in Mougins on Sunday 8 April 1973, at the age of 91. The local authorities would not permit him to be buried there, so his wife Jacqueline chose the grounds of the Château of Vauvenargues as his last resting place. The funeral cortège arrived to find Vauvenargues under a blanket of fresh snow, unusual for that time of year. The event was marred by the complex family problems that had clouded Picasso's final years. Jacqueline denied entry to several close friends and his three estranged children: Maya, Picasso's daughter by his longtime mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter, and Claude and Paloma, his children by Françoise Gilot. Picasso's body lay in a mahogany casket in the vaulted guardroom, the oldest part of the château, during the week it took for a grave to be dug in the shaded terrace in front of the main entrance.

On 16 April his body was placed in the grave in a sleeping position, beneath a mound of earth. Jacqueline had the monumental sculpture Woman with a Vase placed symbolically on the grave and transformed the guardroom into a shrine for her husband, filled with flowers. The sculpture is a second casting of the sculpture of 1933 that had guarded the Spanish Pavilion during the International Exhibition in Paris in 1937, where Guernica was first displayed. (This historic combination of the two works of art has been reintroduced by the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, where Guernica forms the centerpiece of the museum.) [16][17]

Thirteen years later, with the family divided by arguments over the future of the Picasso estate, Jacqueline took her own life. Before her death she had regularly visited her husband's grave on the 8th of every month. Her funeral service took place in the old guard room of the château and she was buried next to Picasso.[18] The ownership of the château passed to Catherine Hutin, Jacqueline's daughter by her first marriage. With her principal residence in Paris, she agreed to allow the château to be opened for public visits from May to September in 2009 for the first time since 1973; the village of Vauvenargues had long before that rejected plans to transform it into a museum. The château is furnished and decorated as Picasso left it; many bronze sculptures remain, although there are no longer any paintings either by Picasso or from his private collection. Public visits to the château resumed in 2010 from June 30 until October 2, with several more rooms opened to house an exhibition of around 60 of Jacqueline Picasso's photographs.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Base Mérimée: PA00081489, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French) Château

- ^ Longnon, Auguste (1973), Les noms de lieu de la France: leur origine, leur signification, leurs transformations, Ayer Publishing, p. 94, ISBN 0-8337-2142-9, reprint originally published in 1920-1929 by É. Champion

- ^ de Courcelles, Jean Baptiste Pierre Jullien (1826), Histoire généalogique et héraldique des pairs de France, pp. 16–17

- ^ a b c Ely 2009, p. 4

- ^ François de Clapiers himself produced a detailed but unreliable "Genealogy of the Counts of Provence, from 577 to the reign of Henri IV".

- ^ Ely 2009, p. 6 « j'étouffais, je quittais mes livres et je sortais comme un homme en fureur, pour faire plusieurs fois le tour d'une assez longue terrasse, en courant avec toute ma force; jusqu'à la lassitude fit fin à la convulsion. »

- ^ The Hierarchy of the Catholic Church

- ^ Ely 2009, pp. 6–8

- ^ Ely 2009, pp. 10–12

- ^ Ely 2009, p. 12

- ^ Ely 2009, p. 16

- ^ Ely 2009, p. 14 « Trop vaste ? Je vais le remplir. [...] Trop sévère ? Vous oubliez que je suis espagnol et j'aime la tristesse. »

- ^ Ely 2009, pp. 12–13 « Cézanne a peint ces montagnes en maintenant j'en suis propriétaire. »

- ^ Ely 2009, p. 18

- ^ Brassaï (1966), Picasso and company, Doubleday

- ^ Ely 2009, p. 35

- ^ Pablo Picasso's Last Days and Final Journey, Time

- ^ Richardson 2001

References

[edit]- Mairie of Vauvenargues, History and heritage (in French)

- Mairie of Vauvenargues, Picasso Year 2009 Archived 2009-03-14 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- O'Brian, Patrick (1976), Picasso: Pablo Ruiz Picasso : a Biography, Putnam, ISBN 88-304-0863-8

- Ely, Bruno (2009), Château de Vauvenargues (in French), ImageArt, ISBN 978-2-9534525-0-1

- Sobik, Helge (2009), Picasso's homes, Feymedia, ISBN 978-3-941459-02-1

- Martin, Russell (2002), Picasso's War: The Destruction of Guernica and the Masterpiece that Changed the World, Dutton, ISBN 0-525-94680-2, description of the Spanish pavilion during the Paris International Exhibition in 1937

- Richardson, John (2001), The Sorcerer's Apprentice: Picasso, Provence, and Douglas Cooper, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-71245-1

- Picasso exhibitions in the south of France, 2009 (in French)

- Pablo Picasso's burial site opened to public, The Daily Telegraph

- Picasso's grave open to visitors after 36 years, The Age

- Pablo's coming home, The Guardian article on the recreation in 2009 of the 1937 display of Guernica and the Woman with a vase in the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid.

- Official webpage for the Guernica gallery in the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (in Spanish)